The Chain of Responsibility pattern passes a request along a chain of handlers, where each handler decides whether to process the request or pass it to the next handler. This behavioral design pattern emerged from the Gang of Four’s work, creating flexible systems that avoid tightly coupling request senders to specific receivers.

Understanding this pattern transforms how you structure code. Instead of rigid conditional logic, you build modular chains.

Supply chain professionals recognize similar principles in operational workflows. Transport compliance follows structured escalation paths. Each party reviews their scope of responsibility before forwarding decisions.

This guide walks through the pattern’s mechanics, implementation steps, and practical applications. You’ll learn when this approach fits your architecture. You’ll see how handlers connect and process requests independently.

What is the Chain of Responsibility Pattern?

Chain of Responsibility belongs to behavioral design patterns. These patterns focus on communication and responsibility assignment between objects.

In the Gang of Four catalog, Chain of Responsibility is classified as a behavioral design pattern focusing on communication and responsibility assignment between objects. The pattern gained widespread adoption after the 1994 publication of “Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software.”

The core intent addresses a specific architectural challenge. You want multiple objects to potentially handle a request. But you don’t want the sender to know which specific receiver will process it.

Its intent is to avoid coupling the sender of a request to its receiver by giving more than one object a chance to handle the request. This separation creates flexible systems where responsibilities can shift without affecting client code.

Core Characteristics of the Pattern

The pattern operates through linked handlers. Each handler maintains a reference to the next handler in sequence.

When a request arrives, the current handler makes a decision. It either processes the request completely, processes it partially and forwards it, or passes it along untouched.

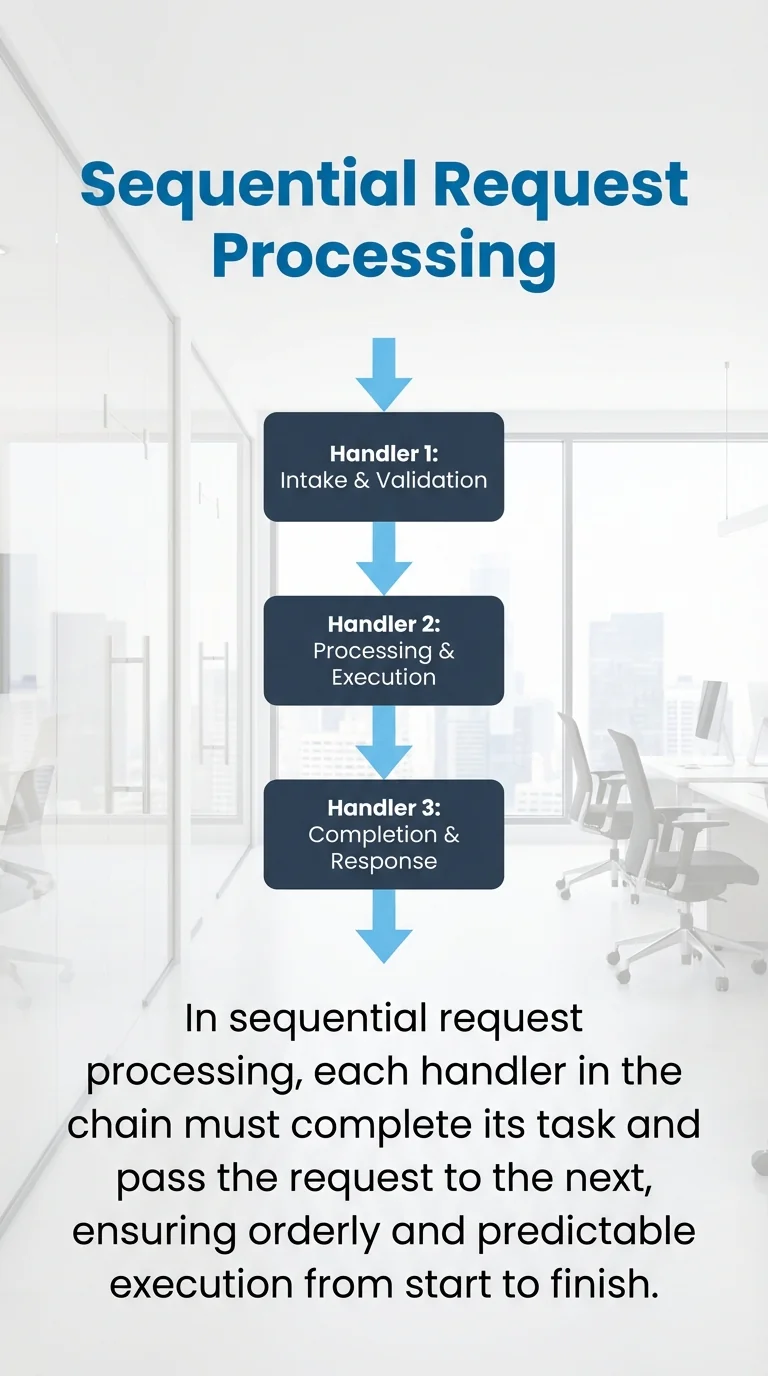

The client sends a request to the first handler, which processes it or passes it to the next until a handler processes it or the chain ends. This sequential processing continues until someone handles the request or the chain terminates.

Handlers work independently. Each focuses on its specific responsibility without knowing about other handlers’ implementations.

How This Differs from Direct Object Communication

Traditional approaches tightly couple senders to receivers. The client code explicitly specifies which object handles each request type.

Chain of Responsibility inverts this relationship. The sender initiates the request without specifying the handler. The chain itself determines the appropriate processor.

This architectural shift provides significant flexibility. Adding new handlers requires no changes to existing client code. Removing handlers simply adjusts the chain structure.

Understanding the Chain of Responsibility Pattern

The pattern solves problems that emerge when multiple objects might handle a request. Traditional approaches use conditional logic to route requests.

Consider a support ticket system. Basic tickets go to junior staff. Complex issues escalate to senior engineers. Specialized problems reach domain experts.

The Limitations of Conditional Logic

Hardcoded if-else chains create rigid structures. Each new handler type requires modifying the routing logic.

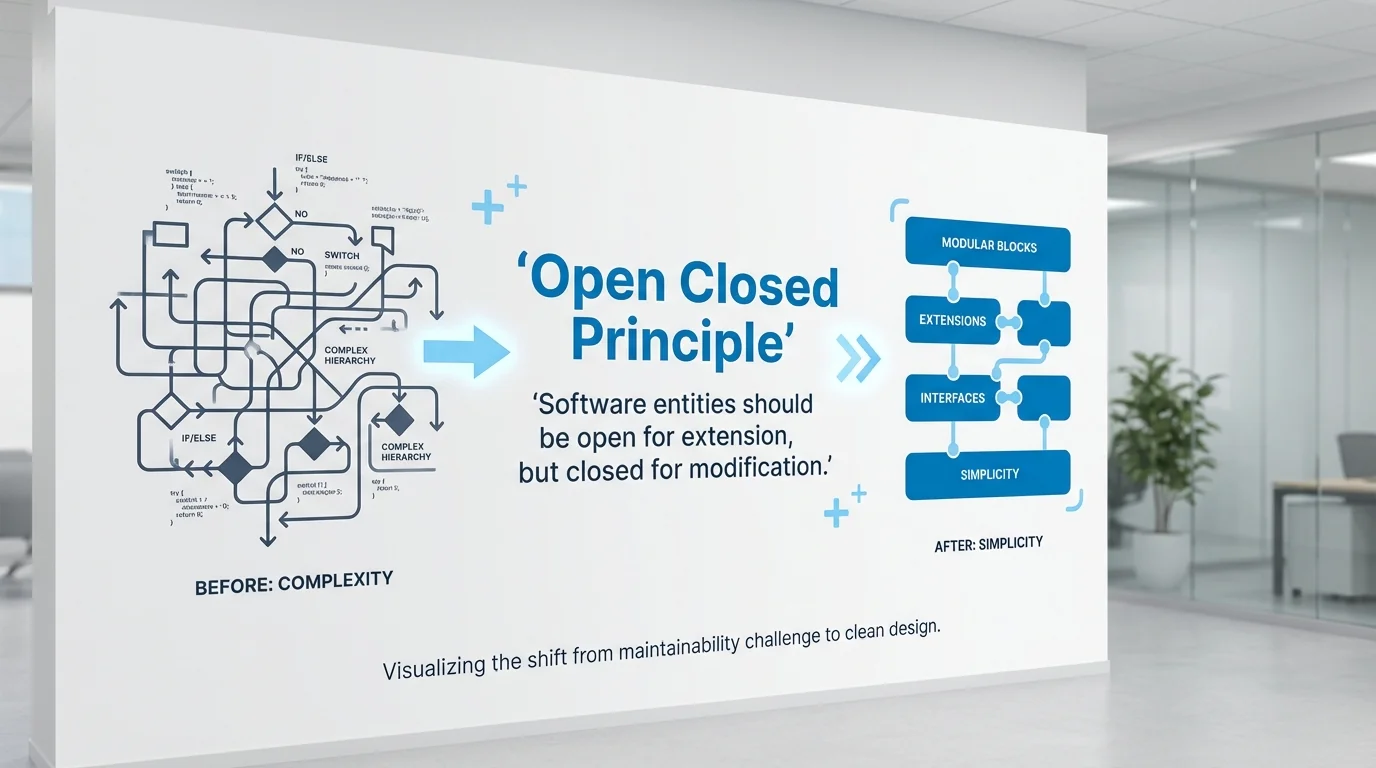

As conditional logic grows, code becomes harder to maintain and extend, which can violate the Open/Closed Principle. You end up changing existing code rather than extending it.

Switch statements face similar issues. Adding cases means touching core routing code. Testing becomes complex as branches multiply.

Error handling gets convoluted. Tracking which handler processes which request becomes difficult. Debugging requires tracing through nested conditions.

How Chain of Responsibility Addresses These Issues

The pattern replaces conditional routing with object composition. Each handler knows only about its immediate successor.

Request processing becomes linear. The request enters at the chain’s start and travels through handlers sequentially.

Provides reusable forwarding logic so each concrete handler can focus on its specific responsibility. Handlers don’t need complex routing logic themselves.

This separation makes testing straightforward. Each handler can be tested independently. Mock objects easily replace chain segments during testing.

When to Consider This Pattern

Chain of Responsibility is recommended when you want to decouple senders from receivers in scenarios where multiple objects may potentially handle a request. Several situations make this pattern particularly valuable.

Use it when processing order is important but handlers might vary. Middleware systems in web frameworks exemplify this perfectly.

Apply it when handlers need dynamic runtime configuration. You might reorder handlers based on user permissions or system state.

Choose it when request handling involves progressive refinement. Each handler adds information or transforms the request slightly.

Real-World Analogy: How Chain of Responsibility Works in Practice

Support escalation systems mirror this pattern perfectly. A customer contacts first-level support with an issue.

The initial handler attempts resolution. They check knowledge bases and apply standard solutions. If they resolve the problem, the chain stops.

When the issue exceeds their expertise, they forward it. Second-level support receives the request with all accumulated context.

Medical Referral Systems

Healthcare follows similar patterns. Patients see general practitioners first. The GP examines symptoms and treats common conditions.

Complex cases get referred to specialists. The specialist might handle it or refer further to sub-specialists.

Each level maintains independence. The patient doesn’t choose specialists directly. The chain determines the appropriate care level.

Context accumulates along the chain. Each practitioner adds notes and test results. The final handler receives complete information.

Approval Workflows in Organizations

Purchase requests follow approval chains. Small purchases might need only supervisor approval. Larger amounts escalate to managers.

Major expenditures reach executive level. Each approver reviews against their authority limits.

The requester doesn’t need to know the complete approval path. They submit once and the system routes appropriately.

Handlers can be added or removed as organizational structure changes. The request submission process remains unchanged.

The Problem: Why Chain of Responsibility Exists

Software systems often need flexible request handling. Multiple objects might be capable of processing a given request.

Traditional approaches create tight coupling. The client must know exactly which object to call. This knowledge creates maintenance burdens.

Avoiding Hard-Coded Dependencies

Direct method calls lock in specific handlers. Changing handlers requires modifying client code.

Consider a payment processing system. Multiple payment methods might be attempted in sequence. Credit card fails, try PayPal, then try bank transfer.

Hard-coding this sequence means changing code for each new payment method. Adding cryptocurrency support requires touching existing logic.

The client shouldn’t need payment method knowledge. It should submit a payment request and let the system determine the method.

Supporting Dynamic Handler Configuration

Business rules change. Processing priorities shift. Systems need runtime flexibility.

Middleware stacks in web applications demonstrate this need. Authentication, logging, rate limiting, and business logic all process requests.

The order matters. Authentication precedes business logic. Logging might surround everything. Rate limiting could apply at different points.

Different routes might need different middleware combinations. Hardcoding these combinations for each route becomes unmanageable.

Managing Unhandled Requests Gracefully

Not all requests get handled. A chain might exhaust all handlers without finding a match.

Traditional systems need explicit failure paths. Each conditional needs an else clause. Each switch needs a default case.

Chain of Responsibility handles this naturally. The request travels through all handlers. If none handle it, the chain simply ends.

You can add a catch-all handler at the chain’s end. This handler provides default behavior or error responses.

The Solution: How Chain of Responsibility Works

The pattern establishes a linked sequence of handler objects. Each handler stores a reference to the next handler.

Request processing follows a clear flow. The client sends the request to the first handler. That handler attempts processing.

Request Propagation Mechanism

Handlers follow a decision protocol. First, check if the request matches their capabilities. If yes, process it.

Processing can be complete or partial. A handler might fully resolve the request and stop propagation. Or it might augment the request and pass it forward.

If a handler can’t process the request, it forwards immediately. Each handler decides whether to process the request or pass it to the next handler.

The forwarding continues until someone handles it or the chain ends. No centralized routing logic exists.

Decoupling Benefits

The sender knows only the first handler. It doesn’t need information about subsequent handlers.

This separation creates powerful flexibility. New handlers insert into the chain without client changes. Handler removal requires only chain restructuring.

Testing becomes modular. Each handler can be tested independently. Integration tests can use partial chains.

Maintenance improves significantly. Changes to one handler don’t ripple through the system. Each handler’s logic remains encapsulated.

Flexibility and Runtime Modification

Chains can be constructed dynamically. You might build different chains based on user roles or system state.

Handlers can be reordered at runtime. Priority processing might move certain handlers forward in the chain.

Conditional chain construction lets you optimize processing. Skip irrelevant handlers entirely rather than letting them pass requests through.

This dynamic configuration supports A/B testing and feature flags. Different user segments can experience different processing chains.

Structure and Components of Chain of Responsibility

The pattern requires several key components working together. Each serves a specific architectural purpose.

Handler Interface or Abstract Class

The Handler defines the contract for all concrete handlers. It typically includes two elements.

First, a method for processing requests. This method receives the request object and attempts handling.

Second, a method for setting the next handler. This allows chain construction through composition.

| Component | Responsibility | Key Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Handler Interface | Define processing contract | handle(request), setNext(handler) |

| Concrete Handler | Implement specific logic | handle(request) with decision logic |

| Client | Initiate request | Send request to first handler |

Base handlers can provide default implementations. They might include forwarding logic to reduce duplication in concrete handlers.

The base handler stores the next handler reference. Concrete handlers inherit this capability automatically.

Concrete Handlers

Each concrete handler implements specific processing logic. They extend or implement the Handler interface.

The implementation follows a standard pattern. Check if the request matches this handler’s responsibility. If yes, process it. If no, forward to the next handler.

Concrete handlers remain independent. They don’t need knowledge of other handlers’ implementations. They know only about their immediate successor.

Multiple concrete handlers can exist in a single system. Each addresses different request types or processing stages.

The Client

The client initiates the processing chain. It creates the request object containing necessary data.

The client sends this request to the first handler. It doesn’t need knowledge of subsequent handlers or processing logic.

Client code remains simple and focused. It constructs the request and triggers the chain. The chain handles all routing and processing decisions.

Request Object

The request encapsulates all necessary information. Handlers access this information during processing.

Requests might be simple value objects. Or they might be complex structures with multiple properties.

The request can carry context accumulated during processing. Each handler might add information for downstream handlers.

When to Use Chain of Responsibility Pattern

The pattern fits specific architectural scenarios. Recognizing these situations helps you apply it effectively.

Multiple Potential Handlers Exist

Use the pattern when several objects might handle a request. You don’t want the sender determining the handler at compile time.

Event handling systems benefit from this approach. Multiple listeners might respond to an event. The order of response matters but shouldn’t be hardcoded.

Form validation provides another example. Different validators check different rules. Each validation step needs independence from others.

Security checks follow similar patterns. Authentication, authorization, rate limiting, and business rules all examine requests.

Processing Order Matters But May Change

Apply the pattern when handler order affects outcomes. The sequence determines final results.

Logging pipelines demonstrate this need. You might log at multiple levels. Request logging, processing logging, and response logging happen sequentially.

Data transformation chains process information progressively. Each step modifies or enriches the data. The order of transformations produces different results.

Caching systems check multiple cache levels. Memory cache first, then disk cache, then database. The order optimizes performance.

Dynamic Handler Configuration is Required

Choose this pattern when runtime configuration matters. Different situations need different handler combinations.

User permission systems work this way. Different roles trigger different validation chains. The system assembles appropriate chains at runtime.

Feature flags can enable or disable handlers. The active chain reflects current feature configurations.

A/B testing benefits from dynamic chains. Different user segments experience different processing sequences.

Avoiding Conditional Complexity

The pattern shines when conditional logic becomes unwieldy. Long if-else chains or switch statements signal this problem.

Each new condition adds complexity. Testing all branches becomes difficult. Maintenance requires understanding the entire conditional structure.

Chain of Responsibility replaces these conditions with objects. Each handler encapsulates one condition. Adding handlers extends functionality without modifying existing code.

How to Implement Chain of Responsibility: Step-by-Step Guide

Implementation follows a systematic approach. Start with interfaces and build toward concrete implementations.

Step 1: Define the Handler Interface

Create the Handler interface first. This establishes the contract for all handlers.

Include a method for processing requests. Name it descriptively, such as handle() or process().

interface Handler {

setNext(handler: Handler): Handler;

handle(request: string): string | null;

}

Add a method for setting the next handler. This enables chain construction.

The handle method returns the result or null. Null indicates the handler didn’t process the request.

Step 2: Create a Base Handler Class

Implement a base handler providing common functionality. This reduces duplication in concrete handlers.

The base handler stores the next handler reference. It implements the setNext method.

abstract class AbstractHandler implements Handler {

private nextHandler: Handler | null = null;

setNext(handler: Handler): Handler {

this.nextHandler = handler;

return handler;

}

handle(request: string): string | null {

if (this.nextHandler) {

return this.nextHandler.handle(request);

}

return null;

}

}

The base handle method provides default forwarding logic. Concrete handlers can override this to add their processing.

Step 3: Implement Concrete Handlers

Create concrete handler classes extending the base handler. Each implements specific processing logic.

Check if the request matches this handler’s responsibility. Process it if applicable. Otherwise, forward to the next handler.

class MonkeyHandler extends AbstractHandler {

handle(request: string): string | null {

if (request === "Banana") {

return `Monkey: I'll eat the ${request}.`;

}

return super.handle(request);

}

}

class SquirrelHandler extends AbstractHandler {

handle(request: string): string | null {

if (request === "Nut") {

return `Squirrel: I'll eat the ${request}.`;

}

return super.handle(request);

}

}

Each concrete handler focuses on its specific responsibility. It doesn’t need knowledge of other handlers.

Step 4: Construct the Chain

Build the chain by linking handlers together. Call setNext to establish the sequence.

const monkey = new MonkeyHandler();

const squirrel = new SquirrelHandler();

const dog = new DogHandler();

monkey.setNext(squirrel).setNext(dog);

The method chaining style keeps chain construction concise. Each setNext call returns the next handler.

You can store the first handler for repeated use. Or create new chains for different scenarios.

Step 5: Send Requests Through the Chain

The client sends requests to the first handler. The chain processes it automatically.

function clientCode(handler: Handler) {

const foods = ["Nut", "Banana", "Coffee"];

for (const food of foods) {

const result = handler.handle(food);

if (result) {

console.log(result);

} else {

console.log(`${food} was left untouched.`);

}

}

}

clientCode(monkey);

The client doesn’t know which handler processes each request. It simply initiates the chain.

Step 6: Handle Edge Cases

Consider what happens when no handler processes a request. The chain returns null by default.

You can add a catch-all handler at the chain’s end. This handler provides default behavior.

class DefaultHandler extends AbstractHandler {

handle(request: string): string | null {

return `Default: No handler found for ${request}.`;

}

}

Position this handler last in the chain. It ensures all requests receive some response.

Advantages and Considerations

The pattern provides several benefits worth understanding. It also introduces considerations for implementation.

Key Benefits

Decoupling stands as the primary advantage. Senders and receivers remain independent. The client doesn’t need knowledge of handler implementations.

Flexibility improves significantly. Add or remove handlers without changing existing code. Reorder handlers at runtime based on conditions.

The Open/Closed Principle gets honored. New handlers extend functionality. Existing handlers remain unchanged.

Testing becomes simpler. Each handler tests independently. Mock objects easily replace chain segments. Integration tests can use partial chains.

Code organization improves. Each handler encapsulates specific logic. Responsibilities remain clear and focused.

Performance Considerations

Long chains impact performance. Each handler adds processing time. Requests might traverse many handlers before finding one that processes them.

Consider chain length in performance-critical paths. Profile actual performance with realistic data.

Optimization might involve reordering handlers. Place frequently matched handlers earlier in the chain.

Some implementations support short-circuiting. Handlers can signal that no further processing is needed.

Debugging and Maintenance

Tracing request flow through chains requires tooling. Add logging to understand which handlers process each request.

Consider adding instrumentation. Track handler execution order and timing. This data helps optimize chain structure.

Documentation becomes important. Clearly document what each handler does. Explain the intended chain configurations.

Version control for chain configurations helps. Track changes to handler ordering and composition.

Chain of Responsibility in Modern Applications

The pattern appears throughout modern software architecture. Understanding common implementation patterns helps apply the design effectively.

Middleware in Web Frameworks

Web frameworks extensively use this pattern. Express.js, Koa, and ASP.NET Core all implement middleware as chains.

Each middleware function represents a handler. Request processing flows through the middleware stack sequentially.

Authentication middleware checks credentials. Logging middleware records requests. Rate limiting middleware enforces quotas. Business logic handlers process the actual request.

Developers configure middleware order through application setup. Different routes can use different middleware combinations.

Event Handling Systems

GUI frameworks use event bubbling. Events propagate through component hierarchies. Each component can handle or pass the event.

Click events might be handled by nested components. The innermost component processes first. If it doesn’t handle the event, it bubbles up.

This pattern allows for both specific and general handlers. A button handles its click. A containing panel might handle unhandled clicks.

Data Processing Pipelines

ETL systems process data through transformation stages. Each stage performs specific operations. Validation, transformation, enrichment, and loading happen sequentially.

Stream processing frameworks apply this pattern. Apache Kafka Streams and similar tools chain processors together.

Each processor receives data, transforms it, and passes it forward. The pipeline structure allows for modular data processing.

Security and Validation Chains

Security systems layer protections. Authentication verifies identity. Authorization checks permissions. Input validation sanitizes data. Business rules enforce domain constraints.

Each security layer operates independently. The chain ensures all checks execute in proper sequence.

Failed checks can short-circuit the chain. A failed authentication prevents subsequent checks from executing.

Quick Answers

What is the correct situation for the use of a Chain of Responsibility pattern?

Use the pattern when multiple objects might handle a request and you don’t want to tightly couple the sender to a single receiver. It works particularly well for building modular processing pipelines such as authentication, rate limiting, and business-rule checks, where each step can independently decide to handle, reject, or forward the request.

When to use Chain of Responsibility design pattern?

Choose Chain of Responsibility when you need to vary or extend request handling logic without modifying the sender or existing handlers. It suits scenarios like HTTP middleware, security filters, and staged validation, where you may add, remove, or reorder handlers dynamically. Following established best practices ensures effective implementation.

How to explain Chain of Responsibility?

The sender doesn’t know which specific object will handle the request. Instead, handlers link together, and each can act or delegate. This supports flexible request processing pipelines where responsibilities split into small, focused handlers that can be combined or changed independently. A comprehensive understanding of the pattern helps explain its mechanics effectively.