The Chain of Responsibility pattern succeeds when handlers stay focused and chains stay manageable. Too many handlers create latency issues and debugging nightmares.

This behavioral design pattern solves a critical problem. It decouples senders from receivers by passing requests through a handler chain.

Each handler decides whether to process the request or pass it to the next handler, creating flexible processing pipelines that adapt to changing business needs.

Think of it like a supply chain approval process. A purchase request moves through supervisors until someone with authority approves it. Each person in the chain evaluates the request based on their responsibility level.

We’ll examine how to structure handler interfaces correctly, keep chains maintainable, avoid common implementation pitfalls, and build systems that scale. You’ll learn practical techniques that prevent the pattern from becoming a performance bottleneck.

What Is the Chain of Responsibility Pattern and Why It Matters

The Chain of Responsibility pattern enables sequential request processing through multiple handlers. Each handler contains logic to either process the request or forward it along the chain.

This behavioral design pattern creates loose coupling between senders and receivers. The sender doesn’t need to know which specific handler will process the request. The chain determines that dynamically at runtime.

Consider a transport compliance system checking vehicle loads. The first handler validates weight limits. The second checks dimension restrictions. The third verifies dangerous goods requirements. Each handler specializes in one responsibility.

The pattern works particularly well for validation pipelines. Middleware systems like Express.js demonstrate this pattern in action, where each middleware layer can modify requests before passing them along.

Sequential processing brings clarity to complex workflows. Instead of one massive conditional block checking everything, separate handlers own specific concerns. This modularity makes systems easier to maintain and extend.

Core Components That Make the Pattern Work

Three essential elements form the foundation of this pattern. The Handler interface defines the contract. concrete handlers implement specific processing logic. The Client assembles and triggers the chain.

The Handler interface typically includes two methods. One processes the request. Another sets the next handler reference. This creates the linking mechanism that connects handlers together.

Concrete Handlers contain the actual business logic. Each handler implements the interface and decides whether to process the current request. If it can’t handle the request, it passes control to the next handler in the sequence.

The Client doesn’t know implementation details. It sends requests to the first handler and trusts the chain to route appropriately. This separation of concerns enables flexible runtime configuration.

When This Pattern Solves Real Problems

Authentication systems benefit significantly from this approach. Token validation happens first. Session checking comes next. Permission verification follows. Each handler addresses one security concern.

Support ticket routing demonstrates practical application. Basic queries go to tier one. Technical issues escalate to tier two. Critical incidents reach specialists. The chain directs each ticket to appropriate resources.

Request filtering in web applications uses this pattern naturally. CORS checks happen early. Rate limiting follows. Input validation comes next. Each layer protects the system from specific threats.

The pattern excels when you need dynamic processing paths. Different request types trigger different handler sequences. The same chain structure adapts to varying business scenarios.

Building Handler Interfaces That Scale

Strong handler interfaces form the backbone of maintainable chains. The interface defines how handlers connect and communicate. Poor interface design leads to brittle implementations.

Keep the interface minimal. Include only essential methods that every handler needs. A typical interface requires just two operations: handling requests and setting the next handler.

Type safety matters when defining request parameters. Generic types or well-defined request objects prevent runtime errors. Clear parameter types make handler responsibilities obvious.

Essential Methods Every Handler Needs

The handle method contains core processing logic. It receives the request object and determines whether to process it. Return types should indicate whether processing occurred or the request moved forward.

The setNext method establishes chain links. It accepts another handler reference and stores it. This creates the sequential connection between handlers.

Consider adding a base handler class. It implements common linking logic that concrete handlers inherit. This reduces code duplication across handler implementations.

| Method | Purpose | Implementation Priority |

|---|---|---|

| handle(request) | Process or forward the request | Mandatory for all handlers |

| setNext(handler) | Link to the next handler in chain | Required for chain assembly |

| canHandle(request) | Check if handler can process request | Optional but improves clarity |

Some implementations benefit from explicit canHandle methods. This separates the decision logic from actual processing. It makes handler responsibilities more transparent.

Designing Request Objects for Flexibility

Request objects carry information through the chain. They need enough context for handlers to make decisions. Too little information forces handlers to make assumptions.

Include request type identifiers. Handlers use these to determine relevance. A priority level helps handlers decide whether they should process the request.

Avoid adding business logic to request objects. They should carry data, not behavior. Keep them simple data structures that handlers can inspect and modify.

Consider immutability for request objects. Handlers can read but not change original data. This prevents unintended side effects as requests move through the chain.

Implementing Concrete Handlers Effectively

Concrete handlers contain the actual business logic that processes requests. Each handler focuses on one specific responsibility. Clear boundaries between handlers prevent overlap.

Start by identifying distinct processing steps. Each step becomes a separate handler. Authentication, authorization, validation, and transformation are common handler types.

Single Responsibility for Each Handler

Every handler should do one thing well. A validation handler only validates. A logging handler only logs. This focused approach makes handlers easier to test and maintain.

Resist the temptation to combine related logic. Separate handlers can be composed differently for various scenarios. Combined handlers lock you into specific sequences.

Name handlers clearly. The name should reveal exactly what the handler does. ValidationHandler, AuthenticationHandler, and LoggingHandler leave no ambiguity.

Processing Logic and Pass-Through Decisions

Handlers need clear criteria for processing decisions. Define explicit conditions that determine when a handler acts. Ambiguous conditions create unpredictable behavior.

Implement fail-fast patterns. If a handler detects a critical issue, it should stop the chain. Don’t pass invalid requests to subsequent handlers.

Return meaningful results. Indicate whether processing succeeded, failed, or the request continued. Calling code needs this information to respond appropriately.

- Check if the handler can process the current request type

- Execute processing logic if conditions match

- Return results or pass control to the next handler

- Log decisions for debugging and monitoring purposes

Consider timeout mechanisms for long-running handlers. Requests shouldn’t hang indefinitely. Set reasonable limits and provide fallback behavior.

Assembling Chains for Maximum Flexibility

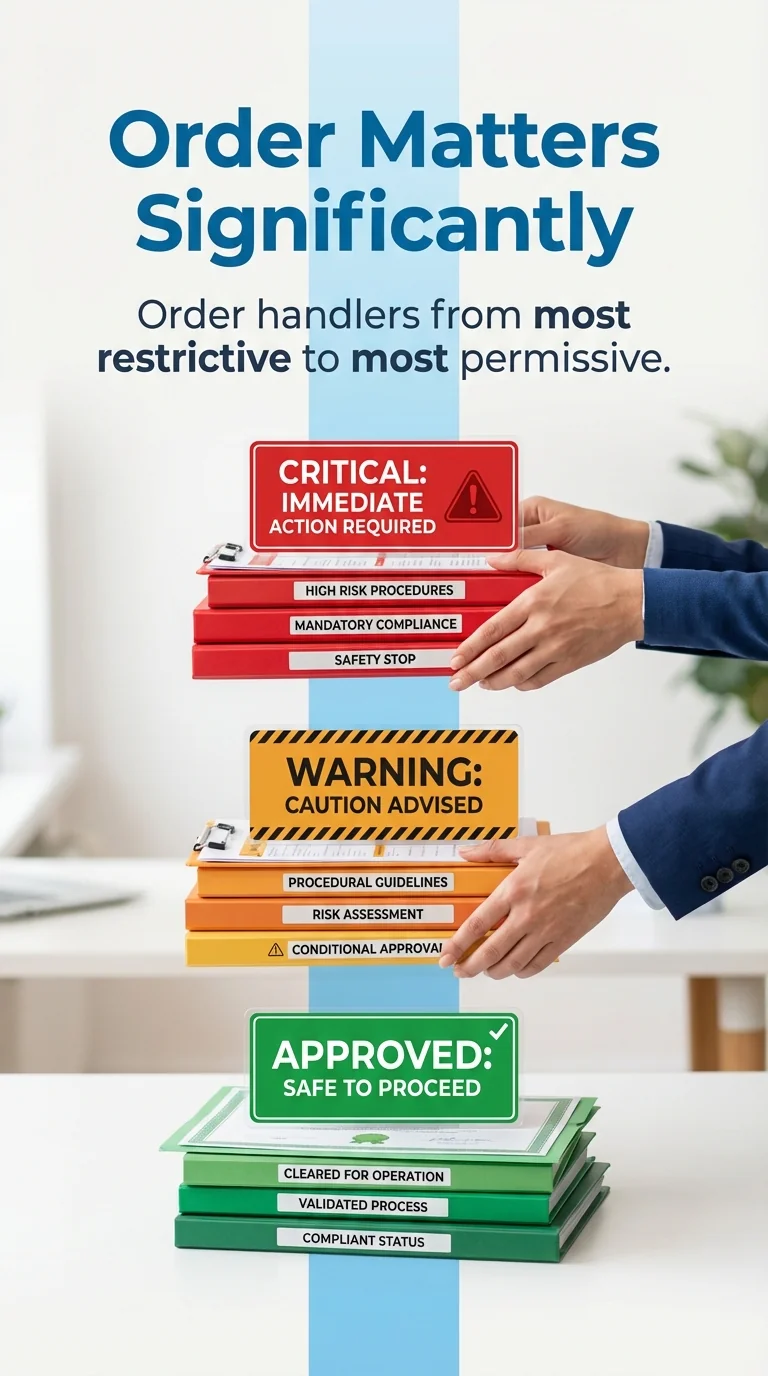

Chain assembly determines processing order and system behavior. The sequence matters significantly. Order handlers from most restrictive to most permissive.

Build chains programmatically rather than hard-coding sequences. Configuration files or builder patterns enable runtime adjustments. This flexibility adapts to changing requirements.

Common patterns place authentication first. Security checks should happen before expensive operations. Validation follows authentication. Processing happens last.

Static vs Dynamic Chain Configuration

Static chains work well for predictable workflows. You define the sequence once at application startup. Simple scenarios benefit from this straightforward approach.

Dynamic chains adapt to runtime conditions. Different user roles might trigger different handler sequences. Request type could determine which handlers participate.

Factory patterns help manage dynamic chain creation. The factory examines request properties and assembles appropriate handler sequences. This centralizes chain logic.

Cache commonly used chains. Don’t rebuild the same sequence repeatedly. Store pre-assembled chains and reuse them. This improves performance.

Managing Chain Termination Conditions

Chains need clear ending conditions. Success might terminate the chain early. Failure could stop processing immediately. Define these conditions explicitly.

The last handler should always have defined behavior. Either process the request or return a meaningful error. Never leave requests unhandled.

Consider default handlers at chain end. They catch requests that no specialized handler processed. This prevents silent failures.

| Termination Type | When to Use | Implementation Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Success Termination | Handler successfully processes request | Return success status, stop chain |

| Error Termination | Handler detects critical failure | Return error status, halt processing |

| End of Chain | No handler processed the request | Default handler or error response |

Avoiding Common Implementation Pitfalls

Long chains create performance problems. Every additional handler adds latency. Keep chains focused. Five to seven handlers typically represents a reasonable maximum.

Circular references cause infinite loops. Handler A passes to Handler B, which passes back to Handler A. Track visited handlers to prevent cycles.

Missing next handler references break chains. Always initialize the next handler field. Null references cause runtime errors when handlers try to pass requests forward.

Performance Considerations and Optimization

Profile chain execution to identify bottlenecks. One slow handler impacts the entire sequence. Optimize or remove problematic handlers.

Asynchronous handlers complicate the pattern. If you need async operations, ensure proper error handling. Don’t let promise rejections crash the chain.

Caching can improve performance for expensive operations. If handlers repeatedly process similar requests, store results. Check the cache before executing full logic.

Monitor chain execution time. Set thresholds for acceptable processing duration. Alert when chains exceed these limits. Slow chains indicate optimization opportunities.

Error Handling Strategies

Decide whether errors should stop the chain. Critical failures usually terminate processing. Minor issues might allow continuation with degraded functionality.

Log errors with context. Include the handler name, request details, and error message. This information helps diagnose problems.

Provide fallback behavior for failures. Instead of returning empty responses, offer reasonable defaults. This improves system resilience.

- Wrap handler logic in try-catch blocks to prevent crashes

- Return error objects that indicate failure type and location

- Implement retry logic for transient failures when appropriate

- Consider circuit breaker patterns for unreliable handlers

Testing Chain of Responsibility Implementations

Test handlers individually before testing chains. Unit tests verify each handler’s logic works correctly. Mock the next handler to isolate behavior.

Integration tests verify chains work together. Test complete sequences from first handler to last. Verify requests flow correctly through the entire chain.

Test edge cases thoroughly. What happens with null requests? How does the chain handle malformed data? Empty chains should fail gracefully.

Unit Testing Individual Handlers

Create focused test cases for each handler. Test successful processing scenarios. Verify the handler processes appropriate request types correctly.

Test rejection scenarios. Confirm handlers correctly pass requests they can’t process. Verify they call the next handler appropriately.

Mock external dependencies. Handlers shouldn’t require real database connections or API calls during testing. Use mocks to control behavior.

Verify side effects. If a handler logs information or modifies state, test those behaviors. Confirm the handler produces expected outputs.

Integration Testing Complete Chains

Build test chains that mirror production configurations. Use the same assembly logic. This ensures tests reflect actual behavior.

Test different request types through the same chain. Verify each type reaches the appropriate handler. Confirm no handlers process inappropriate requests.

Measure performance under load. Send many requests through the chain. Identify memory leaks or degradation. Load testing reveals scaling problems.

| Test Type | Focus Area | Key Validations |

|---|---|---|

| Unit Tests | Individual handler logic | Processing correctness, pass-through behavior |

| Integration Tests | Complete chain behavior | Request routing, sequence execution |

| Performance Tests | Chain efficiency | Execution time, resource usage |

Maintaining and Evolving Chain Implementations

Chains evolve as requirements change. New handlers get added. Existing handlers need modification. Plan for change from the beginning.

Document handler purposes and positions. Explain why each handler exists in the chain. Future developers need this context when making changes.

Version control helps track chain evolution. Tag releases when you modify handler sequences. This enables rollback if problems occur.

Adding New Handlers to Existing Chains

Insert new handlers carefully. Consider where they fit in the processing sequence. Wrong placement breaks existing functionality.

Test thoroughly after adding handlers. Verify the new handler doesn’t interfere with existing ones. Confirm the chain still processes all request types correctly.

Update documentation when adding handlers. Explain what the new handler does. Document any configuration requirements or dependencies.

Consider feature flags for new handlers. This enables gradual rollout. You can disable problematic handlers without code deployment.

Removing or Replacing Handlers

Removing handlers requires careful analysis. Confirm no requests depend on the removed handler. Check that remaining handlers cover all scenarios.

Replace handlers gradually when possible. Run old and new handlers in parallel. Compare results to verify equivalent behavior.

Monitor systems closely after handler changes. Watch error rates and processing times. Issues often appear after deployment, not during testing.

- Analyze which request types the handler processes

- Identify dependencies on the handler’s behavior

- Plan migration path for affected requests

- Implement monitoring to detect issues early

Real-World Use Cases and Applications

Middleware processing represents the most common application. Web frameworks use this pattern extensively. Each middleware layer handles cross-cutting concerns like logging, authentication, and compression.

Event processing systems benefit from this pattern. Events flow through handlers that filter, transform, and route them. Each handler specializes in specific event types.

Transport compliance systems apply this pattern naturally. Load verification happens first. Documentation checks follow. Safety requirements get validated last. Each handler ensures one compliance aspect.

Authentication and Authorization Pipelines

Security systems commonly use handler chains. Token validation happens first. The handler verifies tokens are present and properly formatted.

Session validation follows token checks. This handler confirms the session remains active. Expired sessions stop processing immediately.

Permission verification happens last. This handler checks whether authenticated users have required permissions. Access control rules determine whether processing continues.

This layered approach provides defense in depth. Multiple handlers verify different security aspects. Compromising one layer doesn’t bypass all security.

Request Validation and Transformation

Data validation chains ensure request quality. Schema validation happens first. Handlers confirm requests match expected formats.

Business rule validation follows format checks. Handlers verify requests meet domain-specific requirements. Invalid business logic stops processing early.

Data transformation handlers modify requests. They convert formats, enrich data, or apply defaults. Transformation prepares requests for final processing.

This separation clarifies validation logic. Each handler focuses on one validation concern. Testing becomes straightforward when handlers have clear responsibilities.

Comparing Chain of Responsibility to Related Patterns

The Chain of Responsibility pattern shares characteristics with other behavioral patterns. Understanding these relationships helps you choose appropriate solutions.

Command pattern encapsulates requests as objects. Chain of Responsibility processes those requests through handlers. The patterns often work together.

Decorator pattern also creates chains. However, decorators always delegate to wrapped components. Chain handlers decide whether to process or pass forward.

Chain of Responsibility vs Composite Pattern

Composite patterns create tree structures. Each node contains children. Operations traverse the entire tree structure.

Chain of Responsibility creates linear sequences. Requests move through handlers one at a time. Processing typically stops when a handler succeeds.

Use Composite when operations apply to hierarchical structures. Choose Chain of Responsibility for sequential processing with optional termination.

Chain of Responsibility vs Observer Pattern

Observer pattern notifies multiple subscribers. All observers receive events simultaneously. No observer prevents others from receiving notifications.

Chain of Responsibility processes requests sequentially. One handler might stop the chain. Subsequent handlers never see the request.

Observers work well for broadcast scenarios. Chains suit scenarios requiring conditional processing. The patterns address different communication needs.

Key Principles for Successful Implementation

Successful chains balance flexibility with simplicity. Too much flexibility creates complexity. Too little flexibility limits usefulness.

Start with simple chains. Add sophistication only when requirements demand it. Premature optimization complicates implementations unnecessarily.

Understanding the business value of proper chain design helps justify time spent on careful implementation.

Focus on handler independence. Handlers shouldn’t know about other handlers. They should only know about the Handler interface.

Keep chains short and focused. Long chains indicate missing abstractions. Look for opportunities to consolidate related logic.

Document chain behavior thoroughly. Explain processing sequences and decision criteria. Future maintainers need this context.

Monitor chain performance in production. Track execution times and error rates. Use this data to identify optimization opportunities.

Test extensively at all levels. Unit tests verify handler logic. Integration tests confirm chains work correctly. Performance tests ensure scalability.

Plan for evolution from the start. Requirements will change. Build flexibility into your implementation without over-engineering.

The Chain of Responsibility pattern provides powerful capabilities when implemented correctly. It enables flexible request processing while maintaining clean separation of concerns. Focus on single-responsibility handlers, thoughtful chain assembly, and thorough testing.

Your next step depends on your current needs. Organizations needing enterprise-wide policies should establish clear implementation standards. Teams building new systems should start with simple chains and add complexity gradually. Existing implementations benefit from regular reviews and refactoring.

The pattern succeeds when you resist the temptation to overcomplicate. Keep handlers focused. Keep chains manageable. Keep testing thorough.