Building reliable systems requires proper request distribution across handlers. A robust chain defines clear termination rules where a handler can fully handle the request or pass it along if it cannot or should not act.

The Chain of Responsibility is a behavioral design pattern that distributes a request across a sequence of handlers. Each handler decides whether to process the request or forward it to the next handler in the sequence.

This pattern helps decouple senders from receivers by ensuring the component that issues a request does not need to know which specific object will handle it. The sender simply passes the request to the chain, and the handlers determine the appropriate processing path.

You’ll learn how to structure handler chains, implement flexible request processing, and build systems that adapt to changing business logic. Each section builds practical skills for real-world applications.

Understanding the Chain of Responsibility Pattern

The chain pattern solves a specific problem in system design. When multiple objects might handle a request, you need a way to distribute responsibility without tight coupling.

Think about request processing in large systems. Different handlers validate, authenticate, log, or route requests. Each handler performs specific checks or transformations.

The pattern creates a sequential chain where each handler contains a reference to the next handler. When a request arrives, the first handler decides whether to process it or pass it along.

Core Pattern Characteristics

Every chain follows similar structural rules. A base handler defines the interface for processing requests and storing the next handler reference.

Concrete handlers implement specific processing logic. Each handler checks if it can process the request based on its criteria.

If a handler processes the request, it may stop the chain or continue passing it forward. This flexibility allows layered processing where multiple handlers act on the same request.

Behavioral Pattern Classification

Chain of Responsibility belongs to the behavioral design pattern category. Behavioral patterns define how objects communicate and distribute responsibilities across a system.

The pattern focuses on runtime communication between objects rather than static class relationships. Handlers don’t need compile-time knowledge of other handlers in the chain.

This classification matters because behavioral patterns typically involve dynamic message passing. Objects collaborate to accomplish tasks without rigid structural dependencies.

How the Chain Works in Practice

Request processing follows a predictable flow through the handler chain. Understanding this flow helps you design effective implementations.

A client creates a request and passes it to the first handler. The handler evaluates whether it can process the request based on its responsibilities.

Three outcomes can occur at each handler. The handler processes the request and stops the chain. The handler processes the request and passes it forward. The handler skips processing and immediately forwards the request.

Handler Interface Design

The handler interface defines two key responsibilities. First, it declares a method for processing requests, typically called handle or process.

Second, it provides a mechanism for setting the next handler in the chain. This creates the linked structure that enables sequential processing.

Most implementations use a base handler abstract class rather than a pure interface. The base handler stores the next handler reference and provides default forwarding behavior.

| Handler Component | Purpose | Implementation Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Base Handler | Defines interface and forwarding logic | Abstract class with next handler reference |

| Concrete Handler | Implements specific processing rules | Extends base handler with custom logic |

| Client | Initiates requests to the chain | Calls first handler with request object |

Request Forwarding Mechanics

Each handler contains logic to determine forwarding behavior. Some handlers always forward after processing, creating middleware-style pipelines.

Other handlers forward only when they cannot process the request. This creates a selection pattern where the first capable handler takes responsibility.

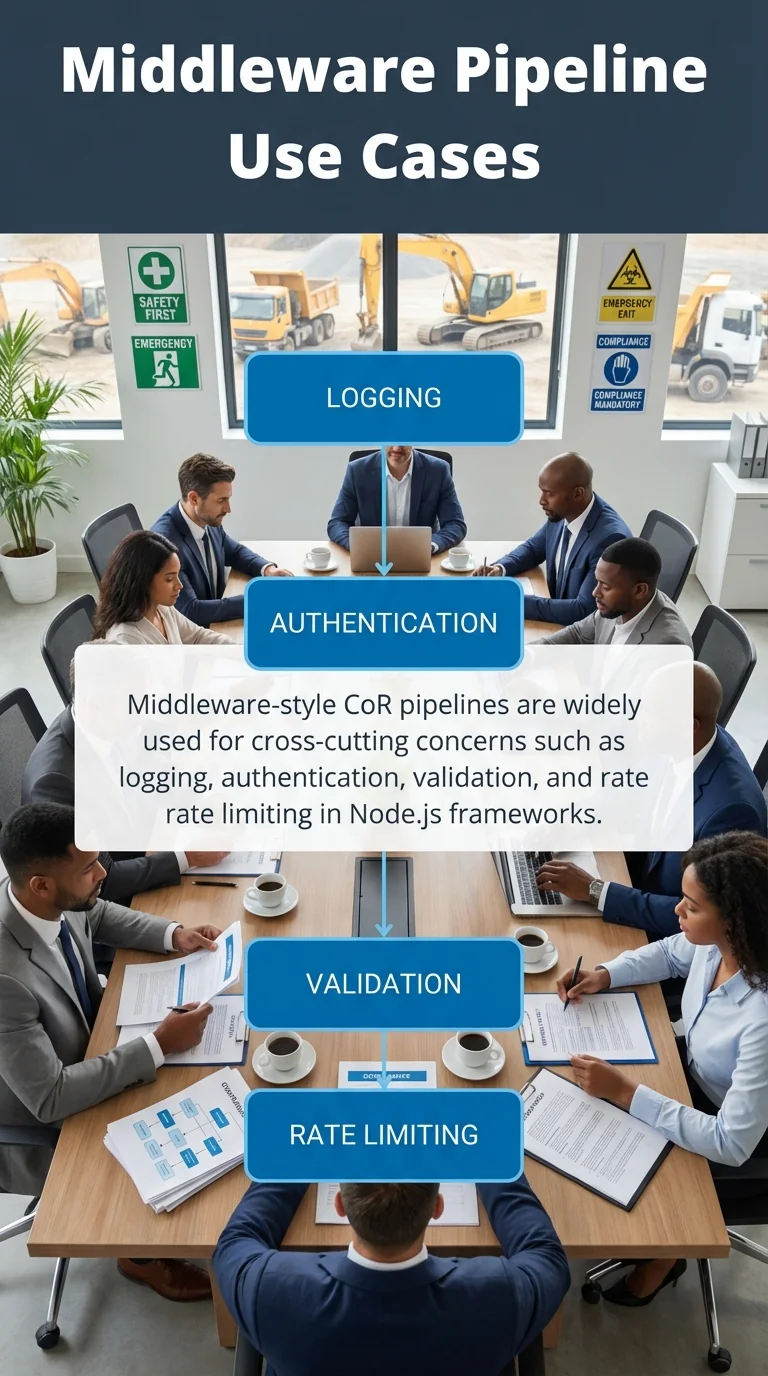

Middleware-style CoR pipelines are widely used for cross-cutting concerns such as logging, authentication, validation, and rate limiting in Node.js frameworks. Each middleware function processes the request and calls the next handler in sequence.

Problem and Solution Framework

Software systems often face requests that require multiple processing steps. Traditional approaches create tight coupling between request senders and receivers.

Direct coupling causes problems when processing logic changes. Adding new handlers requires modifying existing code. Reordering handlers becomes difficult without restructuring client code.

The Chain of Responsibility pattern solves these problems through indirection. The sender only knows about the chain’s entry point, not individual handlers.

Decoupling Senders and Receivers

Traditional request handling creates dependencies between components. The sender must know which receiver handles each request type.

This knowledge requirement scales poorly. Adding new request types means updating sender logic. Changing handler assignments requires modifying multiple locations.

The chain pattern breaks this dependency. Senders pass requests to the chain without knowing the handler structure. Handlers determine routing based on their internal logic.

Dynamic Handler Composition

Chains support runtime configuration of handler sequences. You can add handlers, remove handlers, or reorder them without changing client code.

This flexibility proves valuable for systems with changing business rules. New validation steps can slot into existing chains. Temporary handlers can intercept requests during specific conditions.

The pattern supports conditional chain construction. Different request types might use different handler sequences, all initiated through the same interface.

Structure and Components Breakdown

Every Chain of Responsibility implementation contains four core components. Understanding these components helps you build effective handler chains.

The handler interface defines the contract for processing requests. The base handler provides common functionality for all concrete handlers. Concrete handlers implement specific processing logic. The client assembles and initiates the chain.

Handler Interface Definition

The handler interface declares the primary processing method. This method accepts a request object and returns a response or status indicator.

Most interfaces include a method for linking handlers together. This method typically accepts another handler instance and stores it internally.

interface Handler {

setNext(handler: Handler): Handler;

handle(request: Request): Response | null;

}

The setNext method often returns the handler itself. This enables fluent interface chaining when constructing handler sequences.

Base Handler Implementation

The base handler class implements common functionality shared across all handlers. It stores the next handler reference and provides default forwarding behavior.

This approach reduces code duplication. Concrete handlers inherit the forwarding mechanism without reimplementing it.

abstract class AbstractHandler implements Handler {

private nextHandler: Handler | null = null;

setNext(handler: Handler): Handler {

this.nextHandler = handler;

return handler;

}

handle(request: Request): Response | null {

if (this.nextHandler) {

return this.nextHandler.handle(request);

}

return null;

}

}

Concrete handlers extend this base class and override the handle method. They can call the parent handle method to forward requests after processing.

Concrete Handler Examples

Concrete handlers implement specific processing logic. Each handler checks whether it should act on the request.

A validation handler might check request parameters against business rules. An authentication handler might verify user credentials. A logging handler might record request details.

class ValidationHandler extends AbstractHandler {

handle(request: Request): Response | null {

if (!this.isValid(request)) {

return { status: 'error', message: 'Invalid request' };

}

return super.handle(request);

}

private isValid(request: Request): boolean {

// Validation logic here

return request.data !== null;

}

}

Handlers can choose different response strategies. Some return immediately after processing. Others always forward to the next handler, creating pipeline behavior.

Implementation Steps

Building a handler chain follows a systematic process. Start with interface design, then build the base handler, and finally implement concrete handlers.

Define the handler interface first. This interface establishes the contract all handlers must follow.

Create the base handler class next. This class provides shared functionality for managing the next handler reference.

Step One: Define Handler Interface

Identify the data that handlers need to process. Create a request object that encapsulates this data.

Define the handler interface with two methods. The handle method processes requests. The setNext method links handlers together.

Consider whether handlers should return values. Some chains return processing results. Others use side effects like logging or updating state.

Step Two: Build Base Handler

Implement the handler interface in an abstract base class. Store the next handler reference as a private field.

Implement the setNext method to update this reference. Return the handler instance to enable method chaining.

Provide default handle behavior that forwards to the next handler. Concrete handlers can override this behavior while still accessing the forwarding logic.

Step Three: Create Concrete Handlers

Extend the base handler for each specific processing responsibility. Override the handle method with custom logic.

Each concrete handler should focus on a single responsibility. This keeps handlers simple and promotes reusability.

Decide whether each handler forwards requests after processing. Pipeline-style handlers always forward. Selection-style handlers forward only when they can’t process the request.

Step Four: Assemble the Chain

Instantiate concrete handler objects in the client code. Link them together using the setNext method.

const validator = new ValidationHandler();

const authenticator = new AuthenticationHandler();

const logger = new LoggingHandler();

validator.setNext(authenticator).setNext(logger);

const response = validator.handle(request);

Store a reference to the first handler. The client uses this reference to initiate request processing.

Step Five: Process Requests

Call the handle method on the first handler to start processing. The handler chain manages the request flow automatically.

Handle the response returned by the chain. Some chains return null if no handler processed the request. Others guarantee a response from every request.

Learn more about implementing chain of responsibility in different contexts to see how these steps adapt to specific frameworks.

Practical Implementation Example

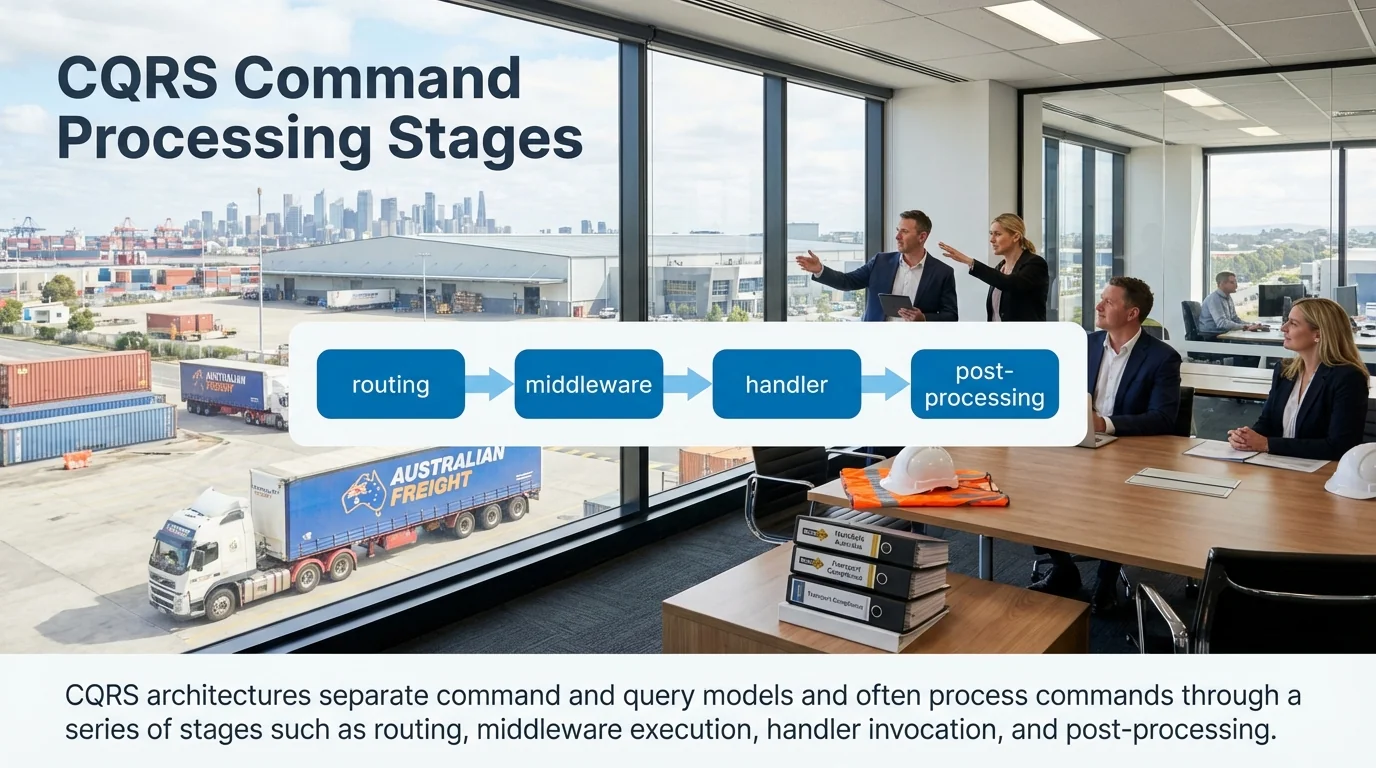

CQRS architectures separate command and query models and often process commands through a series of stages such as routing, middleware execution, handler invocation, and post-processing. The Chain of Responsibility pattern fits naturally into these processing pipelines.

Consider a request processing system that handles user commands. Each command requires validation, authentication, authorization, and execution.

Request and Response Objects

Define clear data structures for requests and responses. The request object contains all data needed by handlers.

interface CommandRequest {

command: string;

userId: string;

data: any;

timestamp: number;

}

interface CommandResponse {

success: boolean;

message: string;

data?: any;

}

These interfaces provide type safety and clarity about data flow through the chain.

Handler Implementation

Create concrete handlers for each processing stage. Start with a validation handler that checks command structure.

class CommandValidationHandler extends AbstractHandler {

handle(request: CommandRequest): CommandResponse | null {

if (!request.command || !request.userId) {

return {

success: false,

message: 'Invalid command structure'

};

}

return super.handle(request);

}

}

Add an authentication handler that verifies user identity.

class AuthenticationHandler extends AbstractHandler {

handle(request: CommandRequest): CommandResponse | null {

if (!this.isAuthenticated(request.userId)) {

return {

success: false,

message: 'Authentication failed'

};

}

return super.handle(request);

}

private isAuthenticated(userId: string): boolean {

// Check authentication status

return userId.length > 0;

}

}

Chain Assembly and Usage

Build the handler chain by linking concrete handlers together. Order matters because requests flow sequentially.

class CommandProcessor {

private chain: Handler;

constructor() {

const validator = new CommandValidationHandler();

const authenticator = new AuthenticationHandler();

const authorizer = new AuthorizationHandler();

const executor = new CommandExecutionHandler();

this.chain = validator

.setNext(authenticator)

.setNext(authorizer)

.setNext(executor);

}

process(request: CommandRequest): CommandResponse {

return this.chain.handle(request) || {

success: false,

message: 'No handler processed the request'

};

}

}

The processor encapsulates chain construction and provides a clean interface for clients.

Advanced Chain Patterns

Some implementations need conditional chains that vary based on request properties. Use factory methods to construct different chains for different scenarios.

Pipeline-style chains benefit from result accumulation. Each handler modifies the request or adds to a results collection.

Explore best practices for chain of responsibility patterns to see advanced configuration strategies.

When to Use This Pattern

The Chain of Responsibility pattern fits specific architectural needs. Recognizing these scenarios helps you apply the pattern effectively.

Use the pattern when you have multiple objects that might handle a request. The pattern works well when the handler isn’t known until runtime.

Suitable Use Cases

Middleware pipelines benefit from the chain pattern. Web frameworks use handler chains for request processing, response transformation, and error handling.

Event processing systems use chains to route events through multiple processors. Each processor might log, filter, transform, or trigger actions based on event data.

Validation frameworks implement chains where each validator checks different aspects of data. Email validators, format validators, and business rule validators work in sequence.

| Use Case | Handler Types | Chain Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Web Request Processing | Authentication, logging, compression, routing | Pipeline with all handlers processing |

| Command Handling | Validation, authorization, execution, auditing | Sequential processing with possible early exit |

| Support Request Routing | Level 1, Level 2, Level 3, specialist handlers | First capable handler stops chain |

| Data Validation | Format, business rules, constraints, relationships | All validators process or first failure stops |

Pattern Applicability Criteria

Apply the chain pattern when request processing logic changes frequently. The pattern makes adding or reordering handlers straightforward.

Use chains when multiple objects might handle a request but you don’t know which one until runtime. The chain determines the appropriate handler dynamically.

The pattern helps when you want to decouple request senders from receivers. Senders only interact with the chain interface, not specific handlers.

When to Avoid the Pattern

Skip the chain pattern for simple, fixed processing sequences. The pattern adds complexity that single-handler solutions don’t need.

Avoid chains when every request must be handled by a specific known handler. Direct method calls work better for deterministic routing.

The pattern creates indirection that can make debugging harder. If request flows are complex, consider simpler alternatives first.

Read the definitive guide to chain of responsibility for detailed applicability analysis.

Advantages and Benefits

The Chain of Responsibility pattern delivers several architectural benefits. These advantages justify the pattern’s complexity in appropriate contexts.

Decoupling between senders and receivers ranks as the primary benefit. Clients don’t need to know which handler processes their requests.

Flexibility and Maintainability

Handler chains support dynamic configuration at runtime. Add handlers without modifying existing code. Remove handlers when they’re no longer needed.

This flexibility reduces the impact of changing requirements. New processing steps slot into existing chains. Temporary behaviors can be injected for specific scenarios.

Reordering handlers becomes straightforward. Change the sequence to optimize processing or meet new business rules.

Single Responsibility Principle

Each handler focuses on one specific responsibility. Validation handlers only validate. Authentication handlers only authenticate. This separation clarifies code organization.

Single responsibility improves testability. Test each handler independently without complex setup. Mock dependencies easily because handlers have focused interfaces.

The pattern naturally supports the Open/Closed Principle. Add new handlers by extending the base handler class. Existing handlers don’t change when you add capabilities.

Enhanced Modularity

Handler chains promote modular system design. Handlers act as independent processing units. Combine them differently for different request types.

Modularity simplifies maintenance. Update one handler without affecting others. Replace handler implementations while keeping the same interface.

Teams can work on different handlers independently. Clear interfaces eliminate coordination overhead.

Runtime Behavior Modification

Some implementations support runtime chain modification. Add handlers in response to system state. Remove handlers when conditions change.

This capability enables adaptive systems. Processing logic responds to load, user preferences, or feature flags.

Feature flags integrate naturally with handler chains. Enable or disable handlers based on configuration without code changes.

Design Patterns and Architecture Integration

The Chain of Responsibility pattern works well with other design patterns. Understanding these relationships helps you build robust architectures.

A robust chain defines clear termination rules where a handler can fully handle the request or pass it along if it cannot or should not act. This principle guides integration with other patterns.

Pattern Combinations

Combine Chain of Responsibility with the Command pattern. Commands encapsulate requests as objects. Handler chains process these command objects.

The Decorator pattern shares structural similarities with handler chains. Both wrap objects to add behavior. Decorators always forward to wrapped objects. Chains conditionally forward based on processing logic.

Use the Chain of Responsibility with the Strategy pattern. Different strategies might require different handler chains. Select the appropriate chain based on the chosen strategy.

Architectural Considerations

Design-pattern training emphasizes that patterns like CoR are most effective when used within SOLID and layered architectures. Handler chains fit naturally into layered systems.

Place handler chains at application boundaries. Use them for request processing in web APIs. Apply them for command handling in domain layers.

Keep chains focused on cross-cutting concerns or sequential processing. Avoid using chains for complex business logic better handled by other patterns.

Testing Strategies

Test handlers individually before testing complete chains. Unit tests should verify each handler’s processing logic and forwarding behavior.

Integration tests should verify chain assembly and request flow. Test that handlers execute in the correct order. Verify early exit conditions work as expected.

Mock next handler references in unit tests. This isolates handler logic from chain structure.

Apply quick tips for chain of responsibility implementation to avoid common testing pitfalls.

Common Implementation Challenges

Developers encounter several challenges when implementing handler chains. Recognizing these issues early helps you avoid them.

Chain termination causes frequent problems. Requests might reach the end of the chain without any handler processing them. Decide how to handle this case consistently.

Handling Unprocessed Requests

Define clear behavior for requests that no handler processes. Some chains return null or empty responses. Others throw exceptions.

Add a default handler at the end of chains when appropriate. This handler processes any request that earlier handlers skipped.

Document chain termination behavior clearly. Clients need to know how to interpret responses from chains.

Performance Considerations

Long chains with many handlers can impact performance. Each handler adds processing overhead even if it immediately forwards.

Profile handler chains under realistic load. Identify handlers that add unnecessary overhead. Consider whether all handlers need to run for every request.

Cache handler chain references when possible. Avoid reconstructing chains for every request if handler order doesn’t change.

Debugging Chain Flows

Request flow through handler chains can be hard to trace. Add logging at chain entry and exit points. Log when handlers forward requests.

Consider implementing chain visualization tools for complex systems. Diagrams showing handler sequences help developers understand processing flows.

Use clear naming conventions for handlers. Names should indicate handler responsibilities and position in typical chains.

Moving Forward with Handler Chains

You now understand how to build flexible request processing systems using handler chains. The pattern provides powerful decoupling between request senders and receivers.

Start with simple chains that solve immediate problems. Add handlers for cross-cutting concerns like logging and validation. Build confidence with the pattern before tackling complex scenarios.

Review your existing code for opportunities to apply the pattern. Look for conditional logic that routes requests to different handlers. Look for processing sequences that change frequently.

The Chain of Responsibility pattern strengthens system architecture when applied appropriately. It promotes modularity, flexibility, and maintainability in request processing logic.

Understand why chain of responsibility matters for broader context on pattern benefits and business impact.

Build handler chains that solve real problems. Focus on clear interfaces and single responsibilities. Your systems will become more adaptable and easier to maintain.